Captain W. W. McCarty’s

History of Prison Life, and Southern Prisons

When I left our landing at McConnelsville some twelve months ago, accompanied by a gallant band of veterans, to rejoin the army of the South-West, I but little dreamed of all the vicissitudes through which I was to pass before I should have the pleasure of seeing the faces of my friends  again. It is true, from an experience of nearly three years in the field, I was not insensible of the dangers from shot and shell. I had thought, too, of the diseases of a sickly Southern clime; but the idea of becoming a captive in the hands of the enemy was a matter which had not for a moment

again. It is true, from an experience of nearly three years in the field, I was not insensible of the dangers from shot and shell. I had thought, too, of the diseases of a sickly Southern clime; but the idea of becoming a captive in the hands of the enemy was a matter which had not for a moment

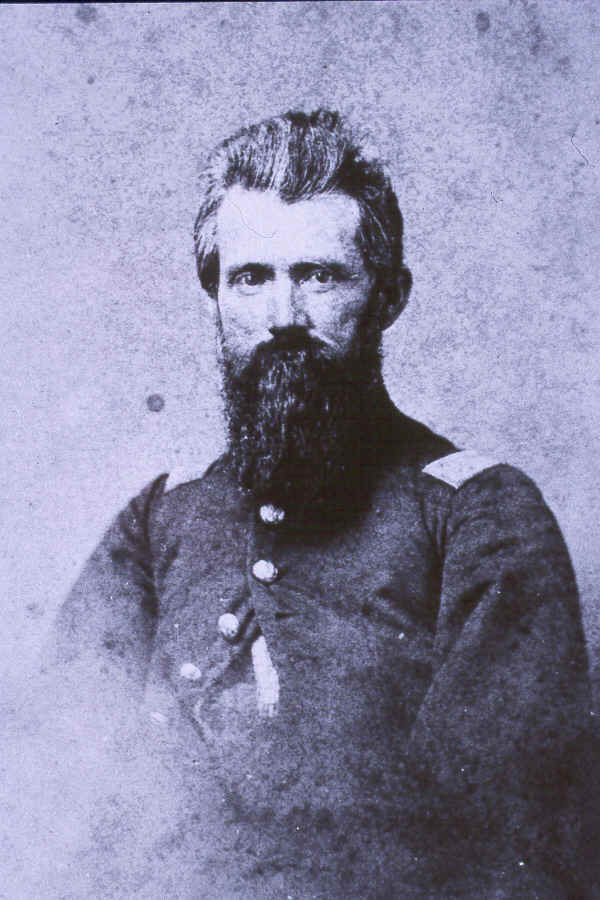

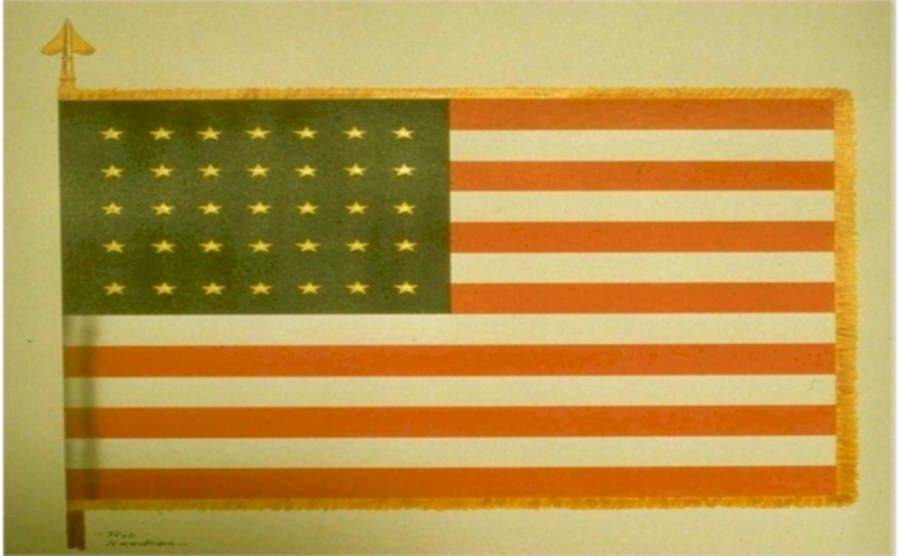

The photos above are (l) the 78th Ohio Battle Flag, courtesy of the Ohio Historical Society, and Capt. W. W. McCarty, courtesy of the U.S. Army Military History Institute, Carlisle Barracks, Carlisle, Pa.

engaged my attention. But that Unseen Power that directs the affairs of men as well as of nations seemed to decree that I should experience the realities of war in all its variety.

On the 19th day of July the Seventeenth Army Corps, after a wearisome march through a portion of Tennessee, Northern Alabama, and across the Sandy mountains of Georgia, a distance of over three hundred miles, driving the enemy before us, we arrived within a few miles of Atlanta, where the rebel General Hood had made a stand. On the morning of the 22d we were attacked on the left flank, and in our rear, by General Hardee’s Corps, that had moved out the night before, while the remaining portion of the rebel army confronted our right. We were soon apprised of the attack by General Leggett, who rode along our line in person, as well as by the rattle of the enemy’s musketry, and frequent visits of the iron messengers sent from the rebel “howitzers.” The conflict soon became terrible, and in the early part of the engagement our brave and gallant commander, Major-General McPherson, fell, which caused for a time great consternation among our troops. But our brave boys of the West were not disposed to let the rebels achieve a victory. They fought with desperation.

The Seventy-Eighth, under command of Colonel Wiles, was occupying a line of breastworks from which we had driven the rebels the day before. These works we were ordered by General Leggett to hold. Inspired with confidence in our gallant Colonel, nearly every man in the regiment seemed determined to see the order carried out or die, and during the struggle several of our brave boys fell, some of them to rise no more. We nevertheless held the entrenchment all day, but were compelled to change front several times during the day, repulsing the enemy in several heavy charges. About half an hour before sun-down, the rebels, who had driven the Thirteenth and Eleventh Iowa regiments, and got possession of the left end of our line of works, opened a heavy artillery fire, raking us with grape and canister.

At this time Colonel Wiles was in command of the Brigade, in consequence of the capture of Colonel Scott, which had taken place during the day. Major Rainey was therefore placed in command of the regiment. Pursuant to orders, we at once vacated the entrenchments and moved out into an open field on our right. Here a Brigade of the rebels, of General Clairborne’s Division, was concealed in a dense thicket of woods near by, and opened a terrific fire upon us. We had nothing to protect us, and the rebels being in close range, protected by the woods, had every advantage. I saw some five or six of the boys of my company shot dead, one of whom was in touching distance of me. The regiment commenced to fall back, when the rebels poured out of the woods as thick as blackbirds, and commenced making prisoners of the wounded. Seeing the regiment receding, I gave orders to my company to fall back with the balance of the regiment, and stepped back a few paces to what had now become our rear, to look after some of the boys who were but slightly wounded, and whom I had hoped to extricate from the danger of being captured by the rebels, by getting them to fall back with the company. Unfortunately, however, I attracted the notice of the rebels, who rallied upon me with furious oaths, the Captain of their gang giving orders to “shoot the d—-d Yankee rascal,” the Captain himself rushing upon me with a nine-inch navy revolver pointing to my breast, and demanding my surrender. By this time some six muskets were pointing toward me, the holders of them awaiting an answer which I was a little show in giving, for, to say I would not surrender, I knew was instant death, and to acknowledge a surrender was one of the most painful events of my life. On a little deliberation I concluded my life might yet be of service to somebody, and thinking it the “better part of valor,” I surrendered with a “mental reservation.” My sword was then demanded by the rebel Captain, who took hold of the belt. I stepped back and commenced to quibble with him about his rank, as he had no insignia of office, and remembering an admonition of my brother the day of leaving Camp Gilbert, never to “dishonor my sword.” I refused to comply with his demand until I became further satisfied that he was an officer of equal rank. By this time Colonel Wiles had arranged our Brigade in a position to repel any further advance of the rebels, and instantly a heavy volley of musketry and artillery came from our line, which frightened my captors no little, and taking advantage of their scare, I threw my sword as far as I could send it in the direction of our own line, where it would have been unhealthy for the rebels to undertake to get it. As the rebel line was now falling back in great haste, they commenced to hurry me, together with four of my men whom they had also captured, off the field.

We were marched to General Hardee’s headquarters, where we were placed under a detachment of Wheeler’s cavalry, and together with about a hundred others of my own Division, were marched into Atlanta by a circuitous route of about fifteen miles, although the place of our capture was only two and a half miles from the city.

In Atlanta many of the prisoners were robbed of their watches, hats, haversacks and rubber blankets by the rebel officers. But as my clothes were old and threadbare, and my appearance rather shabby, they concluded I was not worth robbing, and did not disturb me there. On the morning of the 21st we were taken to East Point, a station on the railroad seven miles south of the city, and ushered into a stockade, with about two thousand other prisoners that had been captured on the 19th, 20th and 22d. Of this number some three hundred were officers, among whom were Colonel Shedd, of the Thirtieth Illinois, Colonel R. K. Scott, of the Sixty-Eighth Ohio, (my Brigade commander) Lieutenant-Colonel C. W. Clancy, of the Fifty-Second Ohio, Lieutenant-Colonel Saunders, of the Sixteenth Iowa, Captain Gillespie of my own regiment, and many others of my acquaintance. We were kept in this pen until the 25th, when we were ordered to Macon, a distance of ninety-six miles south. Although the cars were running through from Atlanta to Macon, the rebel officer informed us we would have to march twenty miles of the way, as the cars on that end of the road were all used in conveying their wounded to the rear, and transporting supplies. Feeling disinclined to do any marching for rebels, I told the rebel officer if he wished me to go to Macon they would have to carry me there, as I was unable to march. He sent Captain Gillespie (who also became indisposed) and myself to the surgeon, who excused us from marching. The balance of them were marched off in the morning, and we remained for the coming train. We spent the day with Major Deacon, the commander of the post, who treated us very courteously, and invited us to dine with him at his quarters. One of the rebel guards informed me that when I would reach Macon I would probably be searched for money before entering the prison. In the evening we were placed upon the cars under a strong guard and started for Macon. I had one hundred and seven dollars in greenbacks, and two dollars and fifty cents of rebel currency in my pocket; and what to do with it become to me a vexed question, as I did not want to lose it, but rather than let it fall into the rebels’ hands I would have torn it up. I at length concluded to try and conceal it, as none of them had yet suspected me of having any. So when darkness set in, and the guards became a little careless and sleepy, I took a ball of yarn which I carried in my haversack for darning my socks, and wrapped it neatly around the folded bills and placed it back again along with my pins, needles, etc. And true enough when we arrived at Macon the first thing on the program was to search us for greenbacks. They turned every pocket, stripped us to the shirt and examined us from head to foot. They then took my haversack and ransacked it. As the officer took the ball of yarn into his hand, I assure you I began to feel a little “weak kneed.” But fortunately he did not mistrust there was any money it, and replaced it in my haversack.

Finding nothing that was attracting about us we were next introduced to the fair ground, which they had arranged for a prisoner’s camp. The ground was enclosed by two lines of fence, the outer one about twelve feet high, and around the top of which the guards were posted at proper intervals, and the inner one, a paling fence about ten feet from the outer one, was the dead line, which it was a death penalty to touch or approach.

On entering the inclosure the cry of “fresh fish! fresh fish!” went up from all parts of the camp, and a general rush was made by about twelve hundred officers of “Libby” notoriety, who gathered around us as though we had come from another world, each trying to catch a word of news. Every now and then the cry would go up from those who could not get up to us, “Louder, old pudding-head!” “O, don’t crowd ’em!” To these ejaculations I at first felt provoked, thinking they were making sport of us, but I soon learned that it was only their mode of initiating new comers. Here I met Lieutenant Paul of Morgan county, Captains Reed and Ross, of Zanesville, Captain Poe, of the Sixty-Eighth Ohio, and “Coon-Skin,” of General Force’s staff; together with many others of my acquaintance.

The old prisoners were quite shabby looking, many of them destitute of shoes and other clothing. some of them had no trowsers, and were going about in drawers. Some of the most destitute ones would steal the meal sacks which the rations of meal was delivered in, and make them up into trowsers. These sacks were all branded in large black letters, “Tax in kind,” as each planter was taxed a certain portion of his products for the support of the army, which was required by their laws to be thus marked. The particular locality of the brand after the sacks were converted into trowsers, was commonly in the rear, a place hard to conceal without a coat, which but few of them had, hence it led to their detection, and rebel officers threatened to cut us short in rations if we used any more of their meal bags for such purposes. As our rations only consisted of a pint of meal per day, a half pint of rice for five days, and a few ounces of bacon, we concluded it would be better to go naked than starve.

The rebel officers here were very tyrannical. On one occasion an officer of the Forty-Fifth New York was shot while returning from the spring where he had been bathing, without any provocation whatever, and no explanation was ever made by the rebel authorities, nor even an investigation of the conduct of the General who committed this willful and deliberate murder.

We had not been long at Macon until one day we heard the booming of cannon, and could see that there was a great commotion among the rebels. We could see them (the citizens) on the tops of the houses looking across the river, and the guards around us were doubled in number. It was Stoneman’s approach, and we were now in high hopes of a speedy deliverance, as we felt assured if Stoneman should enter the town, that we could disarm the guards and join them. But our hopes soon fell to the ground by seeing the next day, Stoneman and a number of his party join us as prisoners of war. This was a hard stroke on the Major-General, but as prison life is a great leveler of rank, he soon eased down and became a common prisoner with the rest of us.

Soon after Stoneman’s capture we were hurried off to Charleston, where it was thought we would be more out of the way of Sherman. On our arrival there, Captain Reed and others escaped and succeeded in reaching our lines. At Charleston we received much better treatment in the way of rations, etc., than we had received at Macon. Although we were under the fire of our own guns, we did not feel much alarmed, as it annoyed the guard more than it did us, and it afforded us a little amusement to see the guards dodging the shells.

Here I received my first letter from home. It was the first time for nine or ten weeks that I had heard one word of information about the fate of my company, or whether my family knew anything of my whereabouts or what had become of me. My mind was relieved of a heavy load of anxiety, but still I was a prisoner. About the middle of September I had a severe attack of intermittent fever, as did also my messmate, Colonel Clancy. We were both sick at the same time. I was taken to a hospital in the city, where, in justice to the rebel surgeon, I feel bound to say I received good medical attention. I only remained here a week, when my chills being checked, I was conveyed to a convalescent hospital three miles from the city, where my medical attention was also good. This hospital was in charge of G. R. C. Todd, a brother-in-law of President Lincoln. The doctor was an ardent rebel, and one incident occurred there which I shall not soon forget. A colored prisoner, belonging to a Massachusetts regiment, who had been taken at Fort Wagner, was accused by the guard of spitting from the portico of the building down into the yard, and without any investigation whatever, the doctor caused him to be stripped and tied, and receive thirty lashes on his naked back. The indignation of our sick prisoners was intense at this brutal treatment inflicted by the hand of a man far inferior to the negro, for the latter could read and write, while the other could do neither and could scarcely tell his name. The negro was a prisoner of war, born and educated in a free State, and he was entitled to the same protection and treatment that we were, and doctor could assign no other reason for his violation of the rules of warfare, than that the boy was a “d—-d nigger.” But perhaps the doctor will apply for pardon now.

I only remained at this convalescent hospital about ten days when I was sent back to the prison. In the early part of October the yellow fever began to spread extensively through the city, and they decided to send us to Columbia; not so much for our safety as for their own, for Sherman was facing toward the coast, and beside our removal was regarded as a sanitary measure for the city. As several exchanges had taken place during our stay at Charleston, our number was now reduced to about twelve hundred, and the most of us regretted to leave, as our quarters here were more comfortable than we expected to get by going to Columbia. But soon the order come, and we were packed into cattle cars and off for Columbia, a distance of 134 miles north of Charleston. We arrived at Columbia on the 5th of October, and from thence conveyed three miles west of the city, where we were placed in an open piece of ground without any inclosure, and simply a camp guard thrown around us. All rations of meat were ordered to be cut off from us and sorghum molasses given in lieu thereof. Hence we called this “Camp Sorghum.” At this camp we annoyed the rebel officers very much by frequent escapes and demoralizing the guard. Two more of our number were shot here without any provocation, while inside the dead-line, and the guards who committed these outrages, we were informed by some of the other guards, received promotions for their villainy. A large majority of the guards were Georgians, and well disposed toward us. The rebel officers could not always watch them, and hence escapes were frequent. At this camp many an amusing incident occurred, one or two of which I propose to introduce in this epistle.

On one occasion, while so many were escaping, the rebel authorities procured the services of a celebrated negro hunter, who kept a pair of blood-hounds that he had trained for hunting down runaway negroes, for the purpose of trailing our escaped prisoners. As the “dorgs” were trotting around the guard lines one morning, some of the prisoners called them into their quarters and cut their throats, and then buried them in an old well which was caved in. About 10 o’clock the dogs were missing, and a detachments of guards sent to search for them. The guards tracked the blood to the old well, and dug them out with their bayonets and reported to the officers, who ordered them to be dragged out of the guard lines, where an inquest was held over them by about two thousand reels. Their first conclusion was that the dogs were dead — the second that some “d—-d Yank” had killed them — and the third, woe be unto the men who destroyed the “purps.” Of course none of us knew who committed the murder, hence investigation was unnecessary. But what was death for the rebs was fun for us.

On another occasion, as we were getting no ratios of meat, and had not had any for fourth months, and some of the more carnivorous had become exceedingly hungry for some, an old black boar came up to the guard lines one day and the guard scared him inside the dead-line. This was no sooner done than the war commenced. About a hundred United States officers of every rank, armed with bludgeons and boulders, attacked his majesty, and in five minutes’ time he was divested of his sable robe and divided and subdivided until every ounce was apportioned out to the hungry raiders, thus affording nourishment to those fortunate enough to come in for a share, and by no means a delightful odor to the hundreds who were less fortunate.

Our rations here were not as good as those furnished to the enlisted men at Andersonville, but as some of us were fortunate enough to have money, we could buy light bread at one dollar and fifty cents per load, the loaf being about the size of a common saucer. We could also buy onions at one dollar each, butter at twenty-four dollars per pound, lard twenty-four dollars per pound, eggs fifteen dollars per dozen, milk, watered to suit the purchaser, at two dollars per quart. I one time thought that something worse than water was in the milk. As one of my messmates and myself were indulging in our “little old pot of mush” and some sky-blue milk, we both became sick at the same time and dropped our spoons, and running to one side vomited profusely. I never was more deathly sick in my life; I thought everything inside of me would come up.

As the rebel officers could not control us very well in “Sorghum,” they removed us to the asylum grounds in the city. These grounds were enclosed by a brick wall about twelve feet high. From this place our only channel of escape was through tunnels, and we had one nearly completed when Sherman frustrated our work by advancing too rapidly upon the city. We were hastened away in great fright to Charlotte, in North Carolina, where we were all paroled for exchange and sent to Raleigh; thence to Goldsboro, thence to Rocky Point, ten miles from Wilmington, where we passed through our lines on the 1st of March, 1865.

Our reception by General Schofield’s army was grand imposing. A magnificently decorated arch of evergreens was erected over the road. On either side the old flag with its stars and stripes was unfurled to the breeze, and as we passed through in four ranks, led by a famous brass band, nearly every heart was ready to burst with joy; and when once through, you would have laughed and cried too, as some of us did, to hear the loud huzzas and seen the old blankets, hats, tin pans and tattered coats, sailing in the air from our liberated prisoners, some of whom had been captives over two years.

We set sail for Annapolis the next day, and on arriving there we immediately divested ourselves of our rags and “creeping things,” putting them in one common pile for conflagration. The next day we had to take the second look to recognize each other, as we were all alike disguised with new suits of clothes.

During my sojourn in rebel prisons, I met with a large number of honest, simple-hearted people, well disposed, and who had no heart in the rebellion. Many also who were extremely ignorant of the cases of the rebellion, or anything connected therewith. I also found, even among the intelligent, some well disposed and gentlemanly officers and citizens; indeed I might safely say that these two classes constituted a majority of those with whom I became acquainted. But among the ringer-leaders and those high in authority, as also some of the “roughs,” I found many who well deserve the rope.

In all my experience, I have never met with a treacherous negro. That there are some, I have not a doubt, but all I met with I found trusty, and many of them more intelligent than the poor whites. The field-hands, however, on the cotton plantations, are very ignorant and debased.

McConnelsville, O., July 10, 1865

Letter Two

Friend Stevenson: — There is one incident connected with my prison life which I omitted in my former letter, and which I now propose to give you.

On the 8th of November, 1864, at 2 o’clock A.M., Captain Turner, of the Sixteenth Iowa, Captain Strang, of the Thirtieth Illinois, Lieutenant Laird, of the Sixteenth Iowa, and myself, made our escape through the guard lines at “Camp Surghum,” near Columbia, South Carolina, with a view of making our way to the gunboats near the mouth of the Edisto river. Having passed through in single file, without drawing a fire from the guard, we struck our way for the timber, and after wandering around an area of some five miles, in search of the Orangeburg road, we at length found ourselves about two miles from camp. As day had now began to dawn, we found it necessary to conceal ourselves. We therefore took refuge in a dense thicket, which was quite narrow, and surrounded by open grounds. Here we remained all day, eating our “corn dodgers,” smoking, making pipes, and whispering over the Presidential election, as we could not talk above a whisper without being discovered or attracting the attention of the dogs and negroes, who were within hearing of us all day. We also speculated a great deal on what we would eat and drink when we would reach our lines. Dark at length came on. The moon shone dimly through the flying clouds, and we moved out quietly in search of the Orangeburg road, which ran directly south from Columbia. After wandering around for some time unsuccessfully, we came across two negro boys, who kindly conveyed us to the road, giving us much valuable information. Once on the right road, we started off in high glee, marching in single file to avoid making too many tracks. To avoid being discovered by any white person was now our chief concern, so we pledged ourselves to one another not to speak above a whisper.

We had traveled about five miles, when suddenly we heard talking ahead of us, and soon discovered a buggy meeting us. We were in an open lane, a board fence on each side, and escape seemed impossible. I gave the signal to the others, which was a shrill whistle, and immediately we all jumped to one side of the road, and fell flat upon the ground, trusting to the brown sage to shield us from the observation of the men in the buggy. They drove up unsuspectingly, until they came opposite to where we were lying, when their horses smelling us, scared and became frantic. The driver struck them with his whip, when they bounded ahead and soon conveyed them out of sight, when we again took the road and made rapid strides on our journey southward. We met two or three wagons during the night, but succeeded in getting out of the road until they passed. They were market wagons on their way to Columbia.

We traveled on until day-break, making a distance of eighteen miles, when we turned aside and selecting a hiding place in the woods we laid down and fell asleep. We remained in this place all day, but were frightened several times at dogs, which were running through the woods in search of something to eat. We were not afraid of the dogs, but only afraid they might bark and lead to our discovery. But the day passed off safely to us, and when darkness come on we again took up our march. Our haversacks by this time were rather light for our health, but we pushed on, hoping to find some friendly negroes by whom we could get them replenished.

After marching a few miles we discovered a light ahead, which we supposed to be in a house, and how to pass it without discovery was now a question of serious moment. As we cautiously moved up a little nearer, the light disappeared, which caused us to change our minds, and our next conclusion was, that it was a rebel picket post. We moved up a little closer, and discovered a bridge between us and where we had seen the last light, which confirmed us in the belief that the bridge was guarded. Captain Strang volunteered to move up close enough to see if he could discover the post and how it was situated. Meanwhile the balance of us concealed ourselves in the bushes by the roadside. The Captain soon returned and reported that he saw a man moving about at the other end of the bridge, but could see no others, strengthening our conviction that the bridge was guarded, and how to get around it was a matter that gave us much trouble. As it was an impenetrable thicket on either side, and the banks of the stream very high.

While consulting what we should do, our ears were greeted by the tread of a “darkie.” Captain Turner stepped to the roadside and attempted to hail him in a whisper. “Uncle! Uncle!” said Turner. “Who dar?” said Harry, in a tone of voice that would have awakened all the pickets within a mile of us. “Hush! hush!” said the Captain, “the picket guards will hear us.” Harry was a little frightened on being hailed so suddenly, and kept on his guard. He had not yet discovered the rest of us. “Who is you?” said Harry, and “what does you want with me?” “We are Yankee prisoners,” said the Captain, “and want to talk with you.” “O! bress de Lord,” said Harry, (Laying down a huge possum which he had suspended by the tail) “Come out, you shan’t be hurt.”

We learned from Harry that there was no guards at the bridge, but that a citizen who was on his way to the coast for salt had put up there for night, and that the light we saw was the man going to the creek to get water for his mules, but that he had gone to sleep in his covered wagon. So, Harry leading off, we set out again, feeling greatly relieved of our troubles. We traveled about three miles beyond the bridge, when we came to the plantation where Harry’s master resided. We stepped into the woods by the road side and set down to rest, while Harry went into the potato patch and grabbed us some sweet potatoes; and after filling our sacks with raw potatoes we renewed our march and continued it till near daybreak.

Before halting, however, we were suddenly alarmed by a signal similar to our own, by the road side, and a man came walking out of the bushes dressed in rebel uniform. He inquired of us something about the roads, supposing at first that we were negroes; but on discovering that we were white he seemed as much alarmed as we were. For a few seconds both parties were afraid to introduce the object of their mission. At length we inquired of him where he was going; he replied that he was going home on a leave of absence. We then asked him what regiment he belonged to. He replied, to a Georgia regiment, but did not recollect the number We then began to see the “Yankee” in disguise, and told him that we were Yankee officers escaping from Columbia prison, which seemed to relieve him greatly, when he acknowledged himself a Yankee also, escaping from Charleston, and trying to reach Sherman’s lines in the direction of Atlanta.

We could give him no encouragement, as he would have two hundred miles to march, under great difficulty. He expressed a desire to join our party, which we would gladly have consented to, but feeling that our party was already large enough, and being fearful that enlarging it would endanger the safety of all, we declined; but giving him our best wishes, we passed on our way until it became necessary to put up for the day. We turned into the first favorable looking place for concealment, threw ourselves upon the ground and soon fell asleep.

But we did not enjoy our repose long. At daylight we were suddenly aroused by the rattle of the cars, which seemed as though they were running over us. On looking around us we discovered that we were only a few feet from the railroad track, and the train had passed by without any one discovering us. But the train once out of sight, we moved further away from the road, and concealed ourselves in a thicket of undergrowth timber, where we ventured to kindle a fire and boil our sweet potatoes. We remained here all day without molestation, though in sight of a plantation house, where we could see the field hands at work. Our provisions had again given out, and when dark set in we attempted to see some of the negroes, but as there appeared to be too many hounds about, we concluded it would be unsafe to remain there, so we struck out for the Orangeburg road. We had got but a short distancee when the roaring of the hounds were heard in our rear, and occasionally the blast of the horn. This alarmed us much, but with cudgels in hand, we made rapid strides toward Orangeburg. We soon became convinced that the hounds were not on our track, but on a fox trail.

As we were evidently nearing the town, we were again troubled to know how we should get around it and reach the river, where we expected to find boats. We struck off on a road which we supposed would take us to the river south of town, but traveling but a short distance we found ourselves in the town, where a retreat was as hazardous as anything else. It was about midnight and the moon shone brightly, so we marched quietly through the village, until we reached the southern boundary, where we chanced to meet a “gentleman of color.” The white people “slumbered and slept.” Our colored friend informed us that there was no boat at the river, but what was guarded by the rebels. We had by this time became exceedingly hungry and tired, but no alternative was left but to push on to some other point. Branchville was our next hope, which was sixteen miles south of Orangeburg and also on the Edisto river. So off we started, taking the railroad track as the safest route. After traveling in this direction two mile, we met a negro man and his wife on their way toward Orangeburg. We found them to be friendly and trusty. The man, whose name was “Toney,” lived a mile further down the road, and his wife lived in Orangeburg. Toney said if we would go on down near massa’s plantation and wait, he would help his wife carry up the forage which they had evidently been getting off massa’s plantation, and return and show us a hiding place, as it was approaching daybreak. We took him at his word, and sure enough, Tony soon returned and conducted us to a dense forest, where we kindled a fire to warm ourselves, and took a short sleep. About 9 o’clock in the morning Toney came out with a basket of provisions, which I assure you we relished. Pone, sweet potatoes, rice, boiled and fried, fresh pork, were luxuries which we did not often indulge in, except the pone.

Tony gave us all the information he could, and stated that his master was an “ossifer in the Conederick States.” He told us if we would remain there until 9 o’clock in the evening, he would bring us some more provisions. We waited accordingly, but Tony failed to appear. We concluded something had turned up, which Tony could not control, so we struck out for Branchville. It was Saturday night, and a good time for meeting darkies, but just at the time we most needed their aid, we failed to meet with any. Traveling on until nearly daylight Sunday morning, we found ourselves in the village of Branchville. We hastened with light steps through the village, and marching about two miles beyond, daylight compelled us to seek refuge in a swampy thicket, where we spent the Sabbath in making pipes. When night came on again, we moved out to the roadside to seek an interview with the first darkie we could see, as it would be impossible for us to travel any further without something to eat, and besides we needed information about the boats. Providentially, we had waited but a few minutes when a half dozen negroes came along, to whom we introduced ourselves, and who seemed glad to see us. They conveyed us to a hiding place, and went to their quarters and cooked us half bushel of sweet potatoes and brought out to us, together with some bread and pork, and a lot of raw potatoes to carry with us. After eating a hearty supper, we gathered up the balance of our “grub,” and “Mose” and the other darkies leading the way, we soon found ourselves at the river, where there were two canoes. Mose owned one of them and his master the other, but Mose said, “Lord a massy, take ’em and welcome.” We paid them a few dollars in Confederate money. Captains Turner and Strang boarded one of the boats, which they named the “Continental,” and Laird and I took the other, which we named the “Gladiator.” Bidding our colored friends good-bye, we pushed out from shore.

“The moon was shining silver bright,

The stars with glory crowned the night,”

and no happier set of fellows could be found than we were when we first struck our paddles in the water of the Edisto, heading toward our gunboats. We made steamboat speed the remainder of the night, and about day-break we tied up and camped for the day, in the wilderness of the Edisto.

Monday night came on, when we again pushed out, and made good speed until three o’clock in the morning, when we again went ashore and took a sleep until daylight, (Tuesday) when we kindled a fire and cooked our remaining potatoes, and sucked our sugar-cane stalks until they were dry. Tuesday night came on, and we resumed our voyage, but it now became necessary to hunt for more forage. So, passing down the river a few miles, we came to a plantation lying near the river, which was quite a rare thing, as it was principally a wilderness on both sides of the river.

Here we pushed ashore, tied our boats under cover of the bank, and moved up quietly to the negro quarters and made ourselves known to darkies, who were glad to see “de Yankees” they had heard so much about; and after becoming satisfied that we had no “horns” and that we were their friends, they rallied all the negroes on the plantation. Women and children came out to see us, each one bringing some token of their kind regard. Even the smallest child had a potato to give us. By these negroes our haversacks were again replenished with grub, but they could give us but little information about what was ahead of us. We started with our treasures to our boats again. Just as I stepped into my boat it tipped up with me, throwing me into the rapid current, and I should evidently have drowned (being no swimmer) but for a bough of a tree which reached to the surface of the water, and which I chanced to get hold of, pulling myself up and climbing up the limb. I again got on shore, and soon we were in our boats and under way. But as I was wet and the night cold, we only traveled a few miles until we went ashore, made a fire, dried my clothes, and slept the balance of the night.

Next day we resolved to run the risk of traveling in daylight, so we pushed out and run at good speed nearly all day, undisturbed save the occasional plunging in of a huge alligator from the shore, which sometimes endangered the safety of our boats. As night approached we were confident that we were nearing a bridge, which we had been previously informed was guarded by rebel pickets, though we could not learn whether we should be compelled to leave them and flank the guards, ruining our chances to get others below the bridge. Our only chances were to “go it blind,” or to see some negroes and get the necessary information.

Darkness at length came on, and we had sailed but a short distance until we heard talking on the shore in the woods, near the river. Supposing it to be the voice of negroes, as it is hard to distinguish the difference between the language of the negro and that of the white man in that country, we pushed ashore, tied our boats, and started up to meet our colored friends, but had got but a short distance when the dogs pitched at us fiercely, and the men began to hiss them on; and advancing rapidly upon us, we soon discovered that we were entrapped.

The party consisted of two white men and two negroes, armed with double-barrel shot-guns, accompanied by two dogs. They demanded of us who we were and where going. We represented ourselves as Confederates on a leave of absence, from the Thirty-Second Georgia. They however mistrusted us, and demanded our papers. I took a piece of paper from my pocket to make believe I had a furlough; but none of the party could read, which was well enough, as there was nothing on it to read. They expressed themselves willing to let us go, if they could do so without their officers finding it out; but said they were under orders to arrest everybody traveling without a pass, and sent for a man in the neighborhood to come and examine our pass. We then told them who we were, as escape seemed impossible, on account of the hounds and other difficulties. We were then taken to a house on the plantation and put under guard, and the women went to work, killed some chickens, went into the field and pulled some corn, shelled and ground it on a little hand mill, baked us a pone from the meal, and made us a supper of chicken, pone and sweet potatoes.

We were now a hundred and sixty-five miles from where we started, and thirty miles south of Charleston. The next morning we were taken to Charleston on the first train. The family where we had stayed all night, being of the poorer class, expressed a good deal of sympathy for us. One of the women remarked to Captain Strang, “Youens are better lookin’ than our folks.”

At Charleston we were introduced to the jail and locked up in close confinement, our rations consisting of a pot of mush a day for all four of us, with nothing to eat it with but our pocket knives and fingers. We were only kept here a few days, however, when we were put upon the cars and returned to Columbia, from whence we started.

Very truly yours,

W. W. McCarty

Play Period Music

“The New Emancipation Song” is used by permission of

Benjamin Robert Tubb from his website at

Public Domain Music